Solving a simple crackmes.one challenge

Recently, I started on with some crackmes.one challenges to finally make a deep dive into reverse engineering world’s. But, the beginning is being completely informal, uncommitted and informal. Otherwise, we need to start with something, right?

The crackmes.one is a place where people cand upload some challenges (programs) and other peoples can make strategies to “hack” the software. Well, you can visit this place on your own.

That’s enough for context, let’s make a deep dive into some initial problems.

The first problem

You can find this problem here.

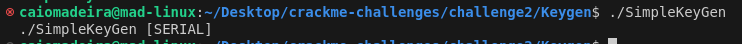

The first problem that I got involved with was ‘The Yuri’s Simple Keygen’ . When I entered this segment of computation (2 weeks ago), this problem was most recommended for everyone. The problem itself is simple. The program is a binary which contains a program written in C and when you run, he asks for a serial key. Obviously, guessing the serial only with some brute force method is out of question here.

The binary is the only information here. We need another approach to make this flow right. And this approach consists in decompiling this binary. We need some kind of disassembler. Of course, we don’t make a disassembler from scratch. In fact, we will use one of the most powerful tools in this area: Ghidra (I do not intend to provide a summary of the tool).

Once we configure the project and open the binary in Ghidra, we can analyse the source code.

Well, maybe part of it.

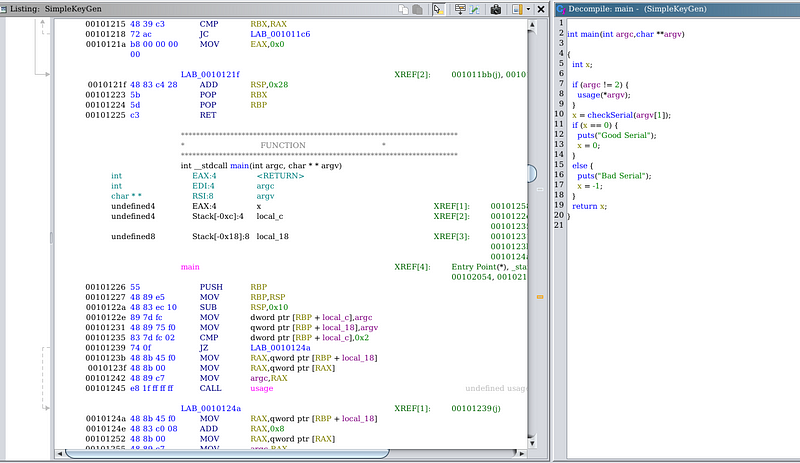

In the Listing view, we can see a disassembled code and the associated data of the program. Machine instructions brought directly into the assembly is what we will see here. This view is our north.

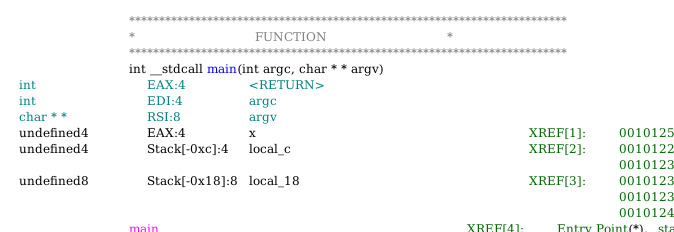

Looking closer, we can see a function declaration in the middle of all these instructions. It’s a well-known main function of C/C++ programs. Well, that’s a start point.

By clicking on this piece of function, we can see an attempt to “translate” it in the Decompile window. The decompile window is, without doubt, one of the most powerful tool in this program. And of course, is a complement of Listing Window, because the assembly code is converted for a more “high-level” presentation. But it’s not always that readable and it is up to us to figure out what piece of code can be.

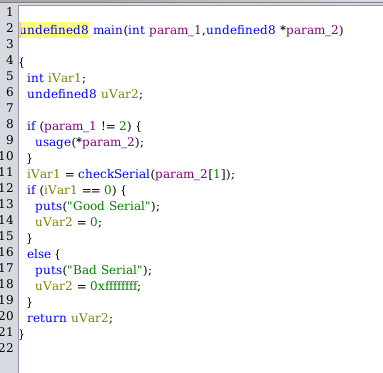

You probably get something like this. And if you know the C basics, it’s easy to decipher this function. So let’s do this.

undefined8 main(int param_1,undefined8 *param_2)

The undefined8 is a way Ghidra says “Hey, i can’t represent this type of data.”. But, if we look in C Standard Library documentation, we can see that’s the name ‘main’ in the function and the two arguments in parameters already give up the points. So this piece looks like this:

int main(int argc, char**argv)

The int argc (int param_1), as well-know, is the amount of arguments which the user pass to the function and the char** argv (undefined8 *param_2) is a pointer to a string array with the arguments. So it’s simple, right? Let’s take a look at the body of function.

int iVar1;

undefined8 uVar2;

if (param_1 != 2) {

usage(*param_2);

}

iVar1 = checkSerial(param_2[1]);

if (iVar1 == 0) {

puts("Good Serial");

uVar2 = 0;

}

else {

puts("Bad Serial");

uVar2 = 0xffffffff;

}

return uVar2;

In the top of the function he waves a couple of variables declared: int iVar1 and undefined8 uVar2. We don’t know both of them, but let’s call the iVar1 as x. But, the type undefined8 for uVar2 is a mystery, so let’s put it aside for now.

In the first condition, we have:

if (param_1 != 2) {

usage(*param_2);

}

We already know the param_2 (argv) and the param_1 (argc). We can translate as:

if (argc != 2) {

usage(*argv);

}

“If the number of arguments is different than two, call the usage function and pass the argv.”

As you can see, we don’t know this function already, but we can assume what he does by the name and context.

iVar1 = checkSerial(param_2[1]);

if (iVar1 == 0) {

puts("Good Serial");

uVar2 = 0;

}

The next piece is this. So let’s translate them.

x = checkSerial(argv[1]);

if (x == 0) {

puts("Good Serial");

x = 0;

} else {

puts("Bad Serial");

x = -1;

}

Remember the x variable (iVar1, for the intimate ones), she makes her reappearance here. As we know, the x receives integer values, and in this case, the variable receives the return value of a mysterious function called checkSerial, which receives as parameter the argument passed by the user. From this, we assume that checkSerial returns an integer (or boolean if you prefer).

And in the end, the program returns the value of x.

So we finally finished our main function and we have some clues that direct us to other parts of the program: the usage() function and the checkSerial() function. Let’s roll over the usage first.

void usage(undefined8 param_1) {

printf("%s [SERIAL]\n",param_1);

/* WARNING: Subroutine does not return */

exit(-1);

}

We can find the function in the same way we found the main one. And the content is very clear. The functions show the user how to use the program, that is, the need to pass a parameter and that parameter is the serial.

If you don’t remember, this function is called when the number of arguments is different than two. So, that’s it. Let’s go to the most important function of this challenge: checkSerial.

undefined8 checkSerial(char *param_1)

{

size_t sVar1;

undefined8 uVar2;

int local_1c;

sVar1 = strlen(param_1);

if (sVar1 == 0x10) {

for (local_1c = 0; sVar1 = strlen(param_1), (ulong)(long)local _1c < sVar1;

local_1c = local_1c + 2) {

if ((int)param_1[local_1c] - (int)param_1[(long)local_1c + 1] != -1) {

return 0xffffffff;

}

}

uVar2 = 0;

}

else {

uVar2 = 0xffffffff;

}

return uVar2;

}

As seen before, the undefined8 in the function signature is clarely int, because we seen your call in main and the parameter (char *param_1) is the argument passed by the user (char** argv).

The news here is the body. We start with a size_t sVar1, and we know what size_t is. The size_t is a type used mainly to store the returned data of sizeof operations. In other ways, he represents the size of objects in bytes. As you can see, the sVar1 is used to store the returned data of strlen(param_1). This function is one of the many others in string.h old header and it returns the size of the given string (param_1). Let’s call the sVar1 with a proper name for the context: size_t len (for length).

So, moving forward and looking over the body, we can assume the type of undefined8 uVar2 is int, because this var is used only to return some feedback as integer. We can do them as int result.

So far we have something like this:

int checkSerial(char *argv)

{

size_t len;

int result;

int i;

len = strlen(argv);

if (len == 0x10)

{

...

}

result = 0;

}

else {

result = 0xffffffff;

}

return result;

}

The core is in if statement. Let’s dive into.

len = strlen(param_1);

if (len == 0x10) {

for (local_1c = 0; sVar1 = strlen(param_1), (ulong)(long)local _1c < sVar1;

local_1c = local_1c + 2) {

if ((int)param_1[local_1c] - (int)param_1[(long)local_1c + 1] != -1) {

return 0xffffffff;

}

}

uVar2 = 0;

}

else {

uVar2 = 0xffffffff;

}

The if condition verifies if the length of string (serial) is exactly 0x10. But, what is 0x10? Is a hexadecimal representation of 16! The decompiler sometimes (based on your configuration) makes things like that with magic numbers. Similar to that, 0xffffffff equals -1. So, if this condition is true, the program runs over the body of the conditional. We found a familiar structure. Is a for statement of course. And you remember the int local_1c? Well, here we have our increment variable. Let’s call them int i.

for (i = 0; len = strlen(argv), i < len; i = i + 2)

The loop starts with int i = 0 (int local_lc = 0), and follows the double condition. The length of string is equal to the length of (argv) (which is a bit unnecessary, btw) and while the value of i is below the length of string, the variable i receives itself plus two. Pay attention to that, because it is important. Indeed, we can ignore this (ulong)(ulong) and just assume the variable as int.

In the for scope, we got some like this:

printf("serial is equal to 16\n");

for (i = 0; len = strlen(argv), i < len; i = i + 2)

{

printf("%c - %c = %d \n", argv[i], argv[i + 1], argv[i] - argv[i + 1]);

if (argv[i] - argv[i + 1] != -1) {

return -1;

}

}

result = 0;

I added some printf calls to make debugging easy.

Anyway, the for runs over the string, char by char and has an internal check which basically asks: “the subtraction of the actual letter and the next is different than -1?”. If the condition is true, the loop immediately breaks and the function returns -1 (“the serial is wrong”). This condition runs for all letters of a single serial. If the condition is satisfied for all pairs of chars, the result is equal 0 and then, the serial is correct.

The program is basically these three functions and it’s pretty simple, but for newbies like me and you, it’s a great initial challenge. But, I haven’t finished yet. What’s the program really?

Conclusion

The program asks for a serial and the serial is a string which conforms with some rules established by the program’s function checkSerial. This function receives the serial candidate and evaluates it.

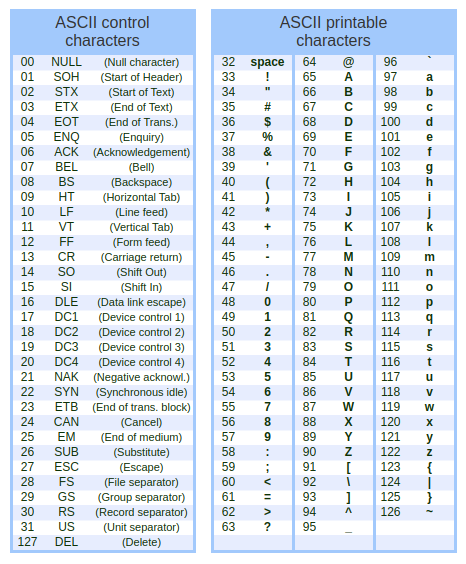

The core of the challenge is to discover the rule to which the serial is subject in and in this case the loop iterates through pairs of characters and do a subtraction with the current by the next. If you don’t remember, a char type value can be represented as an integer, according to the ASCII Table.

ASCII Table

Based in that, i use this string as a valid serial:

./SimpleKeyGen abcdefghijlmnopq

The string contains exactly 16 characters and if you subtract, for example, the first character (a) by the second (b) and look in ASCII Table their respective values (a = 97, b = 98), the result is -1! If you want to really confirm, make for all the others and boom!

Calling some printf functions we got a output like this:

./SimpleKeyGenReversed abcdefghijlmnopq

serial is equal to 16

a - b = -1

c - d = -1

e - f = -1

g - h = -1

i - j = -1

l - m = -1

n - o = -1

p - q = -1

Good Serial

We finally cracked the program!

That’s it for now. I hope you enjoy and feel challenged to get started in this world.

You can check the code in my github repo:

Also you can find me my social networks and poorly made website portfolio:

See you soon.